How Afitpilot came to be.

There’s a moment I keep coming back to. I was sitting in a lecture hall at university, part of a strength and conditioning module, and my coach said something that lodged itself in my brain and never left:

“We don’t have an app for sports periodization.”

That was over a decade ago. I didn’t know how to code. I didn’t have a business plan. I didn’t even fully understand what periodization meant at the depth I do now. But something clicked. I thought: I want to build that.

I didn’t build it then. Life had other plans. But honestly, the story starts long before that lecture hall.

Where it actually began

I grew up in Brussels, and I went to a school called Athénée Robert Catteau — a strict, traditional Belgian school situated at the Place Poelaert, right in front of the Palais de Justice. If you’ve been to Brussels, you might recognise it: that imposing, almost prison-like building sunk into the lower level between Place Poelaert and the Marolles. It looked the part.

I struggled there. Completely. From my first year of primary school, I was suspected of having dyslexia. I was sent to logopédie sessions and gestion mentale — extra-curricular support that happened after school while everyone else went home. From primary through secondary, I was consistently one of the last in my class. And the system made sure you knew it. Test results were handed back from first to last, so every student in the room watched you receive yours at the end. At the annual remise des prix — the prize-giving ceremony — the top students walked on stage, shook hands with teachers, received applause. The rest of us, the three or four kids who’d barely scraped through to the next year, sat in our seats and absorbed the humiliation. Year after year.

On my last year of primary school, my maths teacher Monsieur Henrard pointed at me and my classmate Mehdi in front of the whole class and said: “You two are going to struggle next year.” We were about to enter secondary school. He was right.

Secondary school at Robert Catteau was worse. The humiliation intensified. Teachers treated you like an academic criminal if you were near the bottom. There was clear nepotism. During tests, the students who struggled were made to sit at the front so teachers could keep an eye on us — the assumption being that we were more likely to cheat. I wasn’t cheating. I was drowning.

My only safe place was sport. In primary school I was top of the class in physical education — it came naturally. In secondary, my PE teacher Monsieur Déranger was one of the only teachers who treated me like a human being.

One morning, Monsieur Déranger saw me trying to walk out of the school. I couldn’t take it anymore. I was in tears. He didn’t report me. He didn’t lecture me. He took me out for coffee at the Petit Sablon, and we sat across from each other, and he just talked to me. Kind words. “Don’t you have girls chasing after you?” “You’ve got a great smile.” Simple things that might sound trivial written down, but they stuck with me for the rest of my life. Because he was the only person in that building who was there for me without wanting anything in return. He didn’t do it because he was paid to. He did it because he genuinely cared.

After that, my mum and I decided to get out. She asked me a simple question: “Walter, what do you like doing?” And I said: “Sport.”

So we went looking for sports schools. I ended up at Saint Julien Parnasse, a school with a dedicated sports programme where by the third year you were doing up to eight hours of sport per week. Athletics, team sports, gymnastics, swimming — and you had to be good at all of them. That was how you were evaluated. Not on one discipline. On everything.

The standards were high. You had to run 100m in under 13 seconds. 8km in under 40 minutes. Swim 1km in under 8 minutes. Run 400m in under a minute. Throw javelin over 40 metres. Do a petit allemand in gymnastics. Hold a handstand. Cartwheel. Shot put over 8 metres. Long jump over 3.5 metres. If by your final year of secondary you didn’t have visible abs, something wasn’t right. They weeded out the non-athletic students year by year.

I thrived there compared to Robert Catteau. But looking back now, I see the problems with that system too. There was no science behind it. Just pure performance across every domain. How was any individual supposed to excel at all of these? It was absurd. The curriculum was labelled éducation physique — physical education — but it wasn’t education at all. It was sports performance testing, with no understanding of specificity, no periodization, no acknowledgment that different bodies are built for different things. This is probably where my distrust of imposed institutional curricula began. Who designed this? On what basis? It felt like the Belgian public school approach to everything: shove it down your throat, obey, or sink.

Rugby and the label that stuck

Running alongside school, there was rugby. I started playing when I was six years old and didn’t stop until I was nineteen. In Belgium, our generation was talented — we were in the top division, competition was fierce, and within the team itself we had almost enough players for two full sides, all fighting for a starting spot each match.

It wasn’t easy. When I was twelve or thirteen, I slipped up during a final. I knocked the ball on just before the try line and it cost us the game. After that match, a label stuck. The other players started calling me “butter fingers.” When they were about to pass to me, they’d hesitate — “don’t, he’ll lose it.” That psychological branding reinforced itself. I lost confidence completely.

That label stayed for years. And I made a decision: I would not be humiliated anymore. I started showing up to training three hours early. Practising catching, handling, passing — over and over and over. Not because anyone told me to. Because I refused to let that be my identity.

The respect came back slowly, and then all at once. At eighteen, some of my teammates who played for the Belgian national team recommended me to their coach. I was called up for trials. I was picked. I was now playing for the Belgium U19 national team — internationally, against Romania, Spain, France. I was in the elite.

But I was never a starter. I was the smallest flanker on the squad, 80kg when everyone else was 5 to 10 kilos heavier and 5 centimetres taller. I was reliable. I gave everything. But I wasn’t a talent — not in the way that word gets used when coaches are deciding who to build a team around.

During that time, I noticed something: a lot of the national team players were strong athletes but struggling badly at school. I was approaching my final year and had to make a choice — stay with the national team or finish school as strongly as possible. Playing internationally meant missing academic hours constantly. The pressure was enormous in both directions.

Then I tore my ACL. One year out. Enough time to finish school properly. Things turned out as they should, even if it didn’t feel like it at the time. I never really went back to rugby after that — I played at a decent level in Australia during my gap year, but the chapter was closed.

Finding the thing

After school I was torn between two paths: architecture and sports science. I spoke to two architects who gave me the same advice — don’t do it. Seven years of study, poor pay, limited jobs. The title sounds impressive but the reality is grim. They talked me out of it.

So I chose sports science. And after my gap year, I walked into university genuinely excited to study for the first time in my life.

University was my version of heaven. It made me realise how badly the Belgian school system had got it wrong when it came to sport. At Saint Julien Parnasse, it was labelled éducation physique but it was really just multi-sport performance testing with no underlying science. University taught me why that approach was flawed. It taught me specificity. Periodization. Physiology. Nutrition. Psychology. Biomechanics. Not just academically — we were in the labs, the heat chambers, the altitude chambers, on the force plates, testing pills, measuring strength on machines. It was practical, rigorous, and deeply intellectual.

For the first time, I was surrounded by lecturers who were genuinely curious. The environment wasn’t toxic. It wasn’t political. There was no nepotism, no public humiliation. People just focused on their work and their research. I felt a sparkle in my eye that I hadn’t felt since I was a kid on a sports field. I was thriving.

But I also fell in love with something else. Through an entrepreneurship group called BeePurple, I started hearing stories of people building their own businesses. And I thought: I want that. I don’t want to stay in the academic bubble doing PhDs on questions so specific and impractical they barely touch the real world. I wanted to put sports science into people’s hands. We live in a world of Instagram and bro-science, and I wanted to fight that — to give people access to smart training, grounded in real science, without needing a degree to understand it.

That’s the mindset I was in when my strength and conditioning coach stood up in that lecture and said we didn’t have an app for sports periodization. And that’s why the words hit so hard. Because I already knew I wanted to build something at the intersection of sports science and technology. I just didn’t know what yet.

The long way around

After university, I went into CrossFit coaching. For close to a decade, I coached everyone — competitive athletes, powerlifters, older adults with mobility limitations, people who’d never touched a barbell. I learned more about adaptation, progression, and the gap between theory and practice than any textbook could have taught me.

But I never quite fit in.

Coaching culture, especially in the commercial fitness world, rewards a certain type of personality — high energy, always performing, keeping things light. I took training seriously. Not in a joyless way, but in the way you take seriously anything that has the power to genuinely change someone. I wasn’t there to entertain people. I was there to train them. There’s a difference, and not everyone wants what that actually looks like.

I could never manage more than 10 or 15 clients at a time. Not because I couldn’t handle the hours, but because of how much I put into each person. I was thinking about their periodization, their nutrition, their session design, their progression week to week. Every programme was built with real intent. And honestly? I never felt valued enough for that depth of work. The personal training business model is brutal — people are flaky, uncommitted, and the ones who take it seriously are rare. The economics of trading time for money while pouring that level of thought into each client just doesn’t scale. I knew that even then, I just didn’t have another option yet.

At the same time, I was teaching myself to code. UX design first, then frontend engineering — Vue.js, JavaScript, HTML, CSS. I got jobs in tech. And I found the opposite problem. Development culture could be deeply introverted, heads-down, detached from the physical world I cared about. I wasn’t a pure developer either.

I was somewhere in between — too analytical and intense for the coaching world, too physical and performance-driven for the pure tech world. It took me years to realise that the in-between wasn’t a weakness. It was the whole point.

The moment it clicked

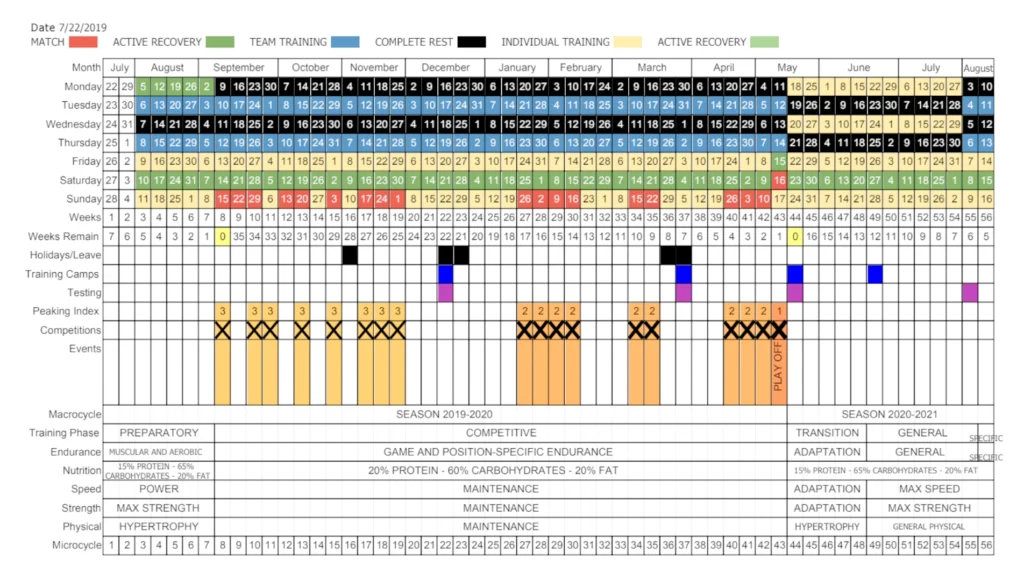

Throughout those coaching years, I briefly took on a strength and conditioning role for my rugby team. I built a full yearly periodised training programme — the kind of thing that takes hours and hours to construct properly. Mesocycles, loading patterns, deload weeks, peaking phases timed to match the competitive calendar. It was thorough. It was structured. It was everything the textbooks say you should do.

You can find the full programme here.

Example of a session plan here.

Then the schedule changed slightly. And the whole thing fell apart.

Not because the programme was bad, but because periodization is a chain of dependencies. You’re not just moving sessions around on a timetable. You’re disrupting the critical adaptations that are supposed to happen in a specific sequence so the athlete peaks at the right time. Shift one block, and the downstream effects cascade through everything — the supercompensation windows misalign, the taper gets compressed, the fatigue management breaks down. Rebuilding it took almost as long as building it in the first place.

That was the moment I understood something clearly: traditional periodization doesn’t fail because coaches don’t know the science. It fails because life doesn’t respect the plan. Schedules change. Athletes get sick. Competitions get rescheduled. And if your programme can’t adapt quickly — faster than any human can reasonably recalculate — it becomes decoration on a spreadsheet.

That experience stayed with me longer than almost anything else from my coaching years. Because it wasn’t just a problem. It was the problem. Periodization doesn’t work unless it’s adaptive. And making it adaptive at speed is exactly the kind of thing that needs technology, not just expertise.

The reason this didn’t exist ten years ago, when my coach first said the words, is that the technology couldn’t do it. Recalculating an entire periodised programme in real-time — adjusting not just schedules but the underlying adaptation logic — requires a kind of reasoning that only became possible with large language models. The science was always there. The compute wasn’t.

Why I take training seriously

There’s a line I’ve been thinking about for a long time: there is nothing better in life than pushing beyond your boundaries.

I don’t mean that in a motivational poster way. I mean it literally. The feeling of discovering you’re capable of more than you thought — more weight, more distance, more resilience — is one of the most honest experiences a person can have. You can’t fake a squat. The bar doesn’t care about your excuses.

And here’s the thing about sports science: it’s usually determined within the boundaries of the general. Research studies need participants, and participants need to consent to uncomfortable things. How many people are going to volunteer for a study that involves running 5km at max effort in a 42-degree heat chamber with an anal thermometer? Not many. So the science, as rigorous as it is, often tells us what’s true for the average person under controlled conditions. It doesn’t always tell us what’s possible for someone who’s willing to go further.

That tension — between what the research says and what individual athletes actually do — is where I’ve always lived. It’s also where Afitpilot lives. The science gives us the framework. The individual defies the boundaries of it.

The somatotype experiment

In 2019, before “vibe coding” was a term, before AI could write a line of JavaScript, I hardcoded my first product. It was a website for what would eventually become Afitpilot, built with Bootstrap, vanilla JS, and HTML. No frameworks. No shortcuts.

https://walter-clayton.github.io/startup/team.html

But the product idea wasn’t training plans — not yet. It was somatotypes.

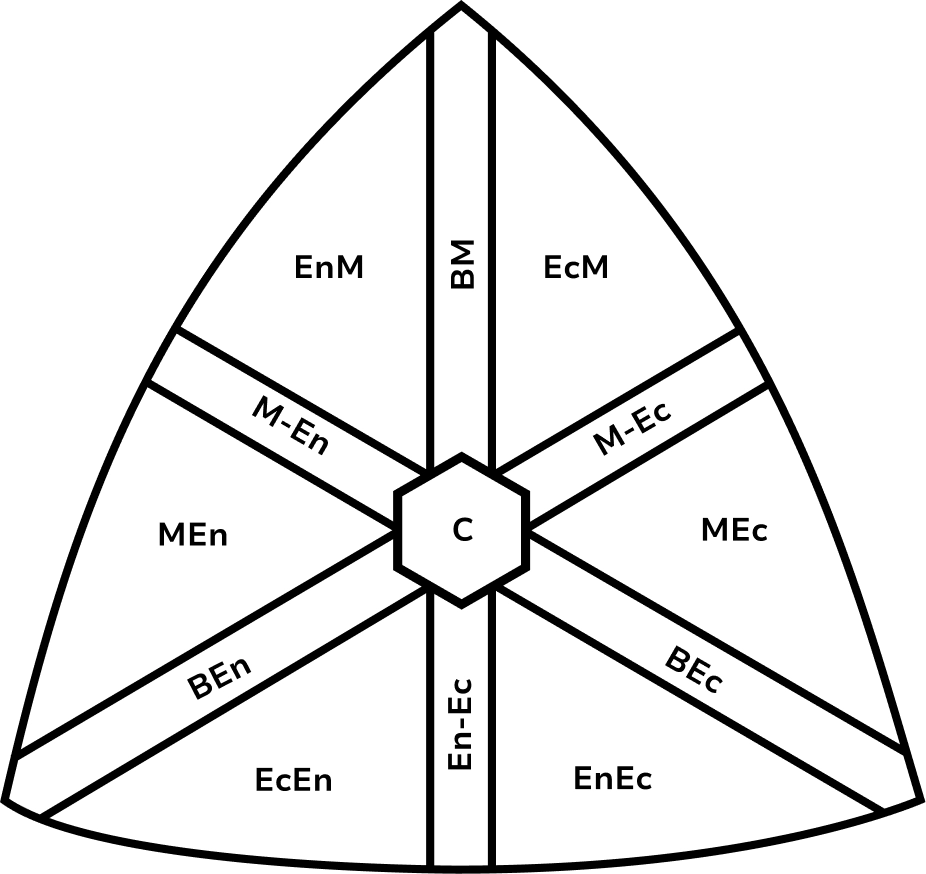

If you’ve ever taken the 16 Personalities test and found yourself weirdly fascinated by the result, that was the energy I was going for. Except instead of personality types, it was body types. The Heath-Carter somatotype method breaks every human physique into three components — endomorphy (fatness), mesomorphy (musculature), and ectomorphy (slenderness) — expressed as a three-number rating. There are 13 distinct somatotype categories, and every person is a unique blend of all three.

I thought: what if people could discover their somatotype the way they discover they’re an INTJ?

So I built a calculator. I wrote the trigonometry to render a somatotype chart on an HTML canvas — the classic triangular somatochart where your three-number rating plots as a single point. I implemented the Heath-Carter equations in JavaScript: the cubic polynomial for endomorphy, the linear equation for mesomorphy, the piecewise function for ectomorphy based on the height-weight ratio. All from the original 2002 instruction manual by J.E.L. Carter.

https://walter-clayton.github.io/somatotype

It worked. It was rough. But the equations were correct and the chart rendered properly.

And if you look at the Afitpilot logo today, you’re looking at that same somatotype graph. I drew it in Figma, manipulating the vertices of the triangular somatochart and playing with the geometry until it felt right as a brand mark. The science is literally in the logo. Most people won’t know that, but now you do.

From calculator to body scan

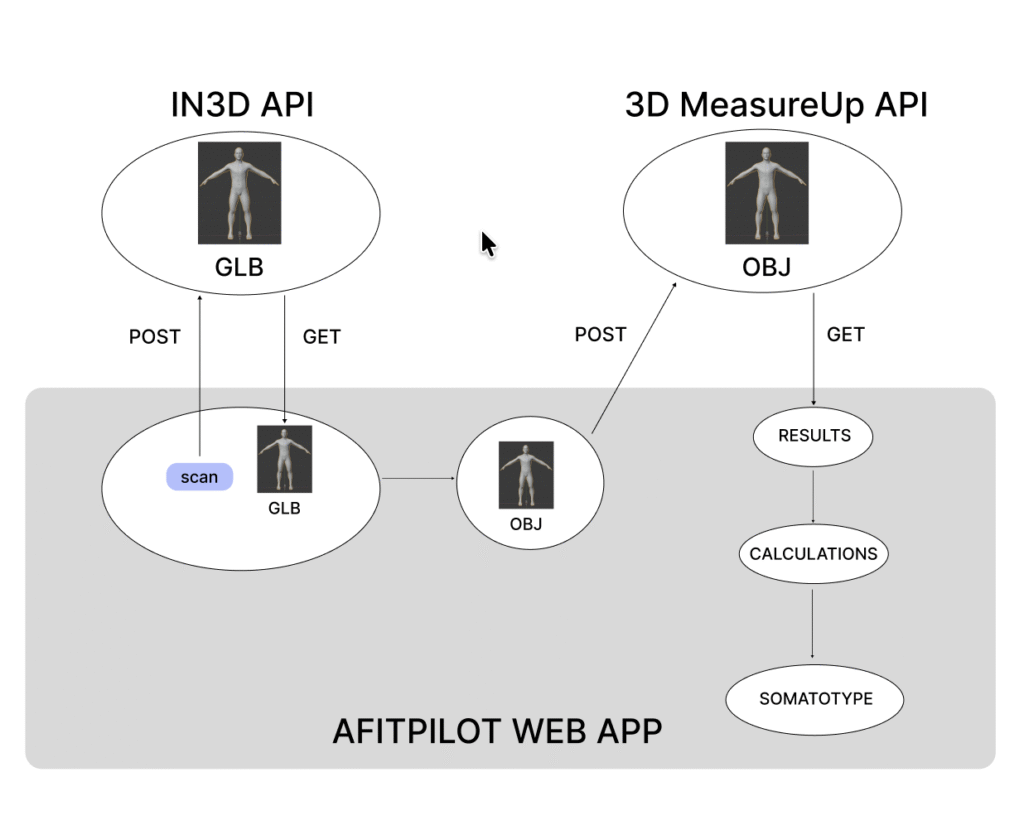

Two years later, I brought on three interns and we built a proper somatotype app — React, Node.js, MongoDB. I handled the science and product design. They handled the code. We shipped it in two months.

https://afitpilot-somatotype.vercel.app

But I wanted to push further. The traditional somatotype method requires skinfold calipers, bone breadth measurements, and a trained anthropometrist. That’s a barrier for 99% of people.

So I wrote a methodology to estimate somatotypes from 3D body scans. Using the in3D scanning API for full-body models and the 3D MeasureUp API for anthropometric extraction, I built a pipeline that could derive the key measurements — height, arm and calf circumference, body volume — and fill in the rest using predictive equations from forensic osteometry and anthropometry research. Femur breadth estimated from height. Humerus breadth derived from femur breadth. Skinfold thickness approximated from body density.

Was it perfect? No. I noted in my own methodology doc that further research was needed on the reliability of some estimations. But it was a proof of concept that the science could be made accessible through technology. That was always the point.

The real product

The somatotype work taught me something important: people don’t just want to know what their body is. They want to know what to do about it.

Knowing you’re a mesomorphic ectomorph is interesting for about five minutes. Knowing how to train and adapt based on your actual physiology, your sport, your recovery patterns, your equipment constraints — that’s valuable for years.

That’s what Afitpilot became. An AI-driven adaptive training platform, engineered to replicate coach-level judgement — the kind of nuanced decision-making that good coaches do instinctively but can’t scale. Right now it’s built for multi-sport athletes, but the architecture is designed to go deeper into sport-specific programming as the AI layers mature. The prompt engineering actually works better when it’s focused and layered correctly, which means the more specific the sport, the sharper the output. That’s the direction this is heading, even if the exact path is still being mapped.

The somatotype work isn’t gone. It’s embedded in the DNA of how Afitpilot thinks about bodies — as unique, multi-dimensional, and responsive to training stimulus in ways that generic programs can’t account for.

The data point I didn’t expect

I need to be honest about something. Since going full startup mode, I haven’t been training as seriously as I usually do. Maybe 80% effort, 80% consistency. I’ve been testing Afitpilot on myself and, if anything, I’ve been mostly underwhelmed by the training it’s generated — which is partly why I’ve been overhauling the AI architecture. I wasn’t exactly peaking.

So when I decided to test my squat and bench press, I was expecting modest numbers. I hadn’t maxed out in years — and the last time I did, I nearly killed myself grinding out 145kg on bench and 195kg on squat.

This time I just casually turned up. Told myself it was about time to see where I’m at. I was expecting maybe 170kg squat and 130kg bench.

I hit 200kg on the squat. 150kg on the bench. No psyching up, no peaking programme, no drama. Those aren’t competition powerlifting numbers, but they’re well beyond what most people who train will ever touch — and I wasn’t even trying to peak.

And then the questions started.

How? I’ve been training less seriously than usual. Have I just grown into a more physically mature body? Is it the creatine I’ve been taking consistently for the past year? The improved sleep? The vitamin D, magnesium, fish oil, B-complex? Some combination of all of it?

And then the bigger questions. I’m casually hitting numbers that suggest serious strength potential I haven’t fully explored. My somatotype — roughly a 2-7-1, heavily mesomorph-dominant — has always pointed toward strength and power sports. Does this mean my highest athletic potential has always been in weightlifting and powerlifting? Should I still bother with hybrid training, constantly fighting the interference effect between strength and endurance adaptations? Have I been training against my own physiology?

And then the product question that I couldn’t shake: should I reintroduce somatotyping into Afitpilot? Not as a novelty feature, but as a genuine input into the adaptive system. If the somatotype can indicate where someone’s natural potential lies, that’s not just interesting information — it’s a training direction. It could give the app a real edge.

Because here’s the uncomfortable question that nobody in fitness really wants to ask: what if you’re training for the wrong sport? What if your body has been telling you something for years and you’ve been ignoring it because you enjoy endurance work, or because your gym culture is built around CrossFit, or because nobody ever showed you the data? That’s not a question most training apps want to touch. It might be exactly the one Afitpilot should.

I didn’t come to fitness tech from a startup accelerator or a product management career. I came from the gym floor, and apparently I’m still generating data that surprises me.

The thread that held

Looking back, the path looks like this: a strict Belgian school that nearly broke me, then sport as the only safe place, then rugby and the national team, then a torn ACL that redirected everything, then university and the first taste of real intellectual freedom, then coaching and hands-on sport science, then self-taught coding and tech careers, then everything converging into what I’m building now.

It wasn’t a straight line. There were years of just surviving — getting jobs, building independence, figuring out what kind of builder I actually was. Years of feeling like I didn’t belong in any single discipline, until I realised that the thing I was building needed someone who didn’t.

Afitpilot needed a coach who understood periodization at a deep level. It needed a designer who could think about user experience. It needed an engineer who could build the whole thing. And it needed someone who took training seriously enough to know when the science stops and the individual begins.

I should be honest: Afitpilot is still changing. I’m still figuring out the positioning — who exactly this is for, how to describe it in a way that sticks. I’ve been saying “hybrid, serious, multi-sport athletes” but I’m not sure that’s quite right yet. The product is evolving, and so is my understanding of where it fits. That’s uncomfortable, but it’s also how real products get built. You don’t find product-market fit in a pitch deck. You find it by shipping, listening, and iterating.

That’s me. That’s always been me. I just needed a decade to build the version of myself who could actually ship it.

And I’m still shipping.

Afitpilot is an AI-powered adaptive training platform for multi-sport athletes. If you train across disciplines and want programming that adapts when life doesn’t go to plan — start here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.