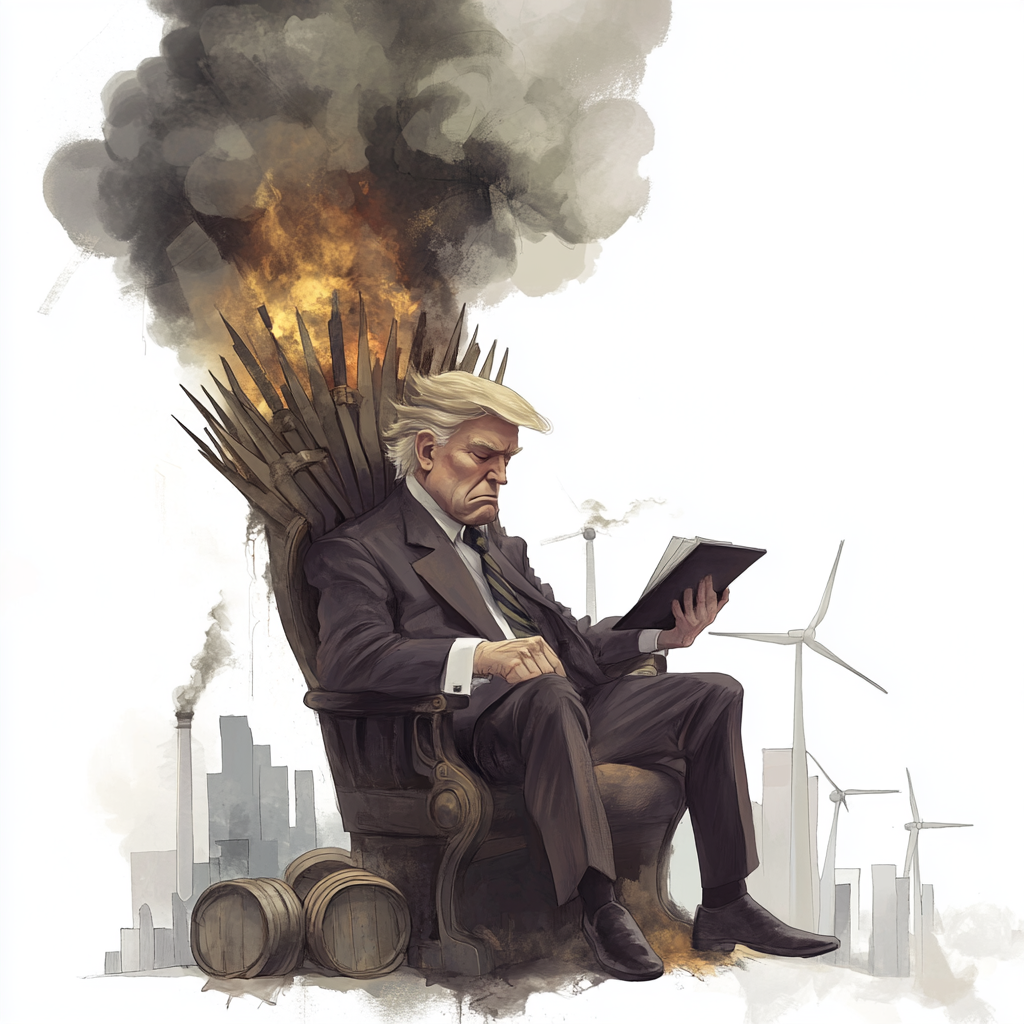

The headlines are buzzing: prominent tech moguls, including vocal climate advocates like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, were seen attending President Trump’s inauguration (see here). Trump, a well-known climate change skeptic, stands at odds with the values these leaders claim to champion. This unexpected alignment has sparked accusations of hypocrisy, corruption, and moral compromise. But is this purely a matter of ethics, or does it reveal something deeper about human psychology?

You’ve heard the warnings: rising sea levels, runaway wildfires, and collapsing ecosystems (see here). The science is clear, the evidence undeniable. And yet, for all our collective knowledge, humanity is stumbling into the future like a sleepwalker heading toward a cliff. Why? The answer lies in the fascinating (and frustrating) quirks of human psychology.

We’re not inherently careless or selfish—we’re just wired to focus on the here and now. From climate change to personal health, our brains are masters at prioritizing short-term benefits over long-term consequences. Here’s why we do it, and how we can fight back against our own worst instincts.

The Science of Short-Sightedness

1. Present Bias: The Now Always Wins

Our ancestors lived in a world of immediate threats and rewards. Eat that ripe fruit before it spoils. Run from the predator before it’s too late. Evolution rewarded those who focused on the present, not the distant future. Fast forward to today, and we’re still living with the same wiring.

- Example: In a classic study on temporal discounting, people consistently chose smaller rewards now over larger rewards later. Why wait a year for $100 when you can have $50 today? As a result, people often prioritize today’s comfort over tomorrow’s gains.

Unfortunately, this instinct doesn’t just apply to money. It’s why we procrastinate on climate action or skip the gym even though we know it’ll hurt us later. For example, nations struggle to agree on emissions reductions because the economic benefits of delaying action seem more tempting in the short term.

2. Optimism Bias: Ignoring Personal Risk

Have you ever heard a smoker say, “I know smoking is bad, but I’ll probably be fine”? That’s optimism bias in action. We underestimate the likelihood of bad things happening to us personally, even when we acknowledge the risk exists for others.

- Fact: Studies show smokers consistently rate their own risk of lung cancer as lower than the average smoker. This same mindset explains why many people downplay the urgency of climate change or fail to save for retirement. As a result, people resist change because they believe disaster is unlikely in their lifetime.

3. Hyperbolic Discounting: The Future Feels Less Important

The further away a consequence is, the less motivated we feel to act. This is known as hyperbolic discounting, and it’s why the abstract idea of “sea levels rising by 2100” feels less urgent than a rise in gas prices tomorrow.

- Example: People are more likely to support climate action when it’s framed around immediate local impacts, like “wildfires in your region” versus “rising global temperatures.” Moreover, companies may delay sustainability measures because immediate profits outweigh long-term risks.

4. The Tragedy of the Commons: Collective Inaction

When resources are shared, individuals tend to act in their own self-interest, even if it’s to the detriment of the group. This phenomenon, known as the tragedy of the commons, is a major driver of overfishing, deforestation, and carbon emissions.

- Fact: In one study, participants were given access to a shared resource and told to manage it sustainably. Even when warned about overexploitation, most continued taking more than their fair share, depleting the resource. Clearly, collective responsibility is difficult to sustain without clear incentives.

What Does This Mean for Climate Change, Health, and Beyond?

These psychological tendencies explain why we’ve been so slow to act on massive long-term problems like climate change, obesity, or rising healthcare costs. The consequences feel distant, abstract, or someone else’s problem—until they’re not.

The result? By the time the “future” becomes the “present,” it’s often too late to avoid the worst outcomes. Think of the millions who only quit smoking after a cancer diagnosis, or governments scrambling to address climate disasters they ignored for decades.

But what happens when influential individuals, who have long been vocal about these very issues, appear to act against their stated values? The recent controversy surrounding tech moguls attending President Trump’s inauguration—despite his well-known climate change denial—is a case in point. Consequently, this situation forces us to question how deeply their advocacy runs.

Leave a Reply